SHAHIN RABBANI

|

The Experience Monkey the writer once famously said: ms,dnf2woksdf,m2mnsd,vsdfs dlfkj32lkj13fjds0vdci[vsdf'RightHere!c;v,erf.s;lj;wef'scvj'erdv,we4i203r20f2fYouFool!0p3l;wdc,snvv3i0rfokdmv,dmcvn'el130eiksds xvcbajkshdq'opwd;wdjfkjerhgHahaYeahNowYouSeeIt!0243857tue'pdokdlvms,mcn.kjjh;I'mshakespeareFU3dkjjd40lgklkjsiowdf;r 'dcv,.dv,bmnyYjsdhp024;;sdmo34i875897y3p02[peijlkfjdkl.efe

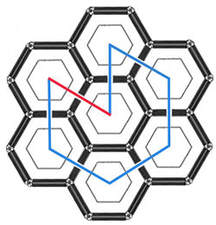

"The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries…The arrangement of the galleries is always the same: Twenty bookshelves, five to each side, line four of the hexagon's six sides…each bookshelf holds thirty-two books identical in format; each book contains four hundred ten pages; each page, forty lines; each line, approximately eighty black letters."

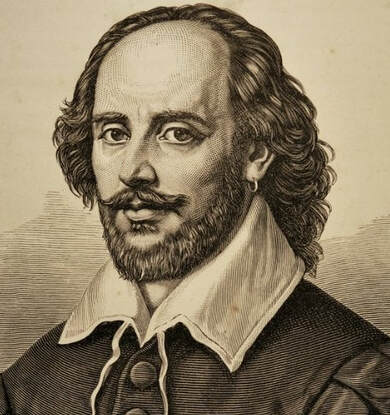

Go to https://libraryofbabel.info/ And Browse->Chamber->Wall->Shelf->Volume->Page with any number you want. Stare at the page for a minute. See if you see things. Then hit "Anglishize". Now you might see some more odd, but legit, words. Even what the monkey is saying on top of this post is in Babel. To be exact, here Title: vfnkeaxl Page: 264 Location: https://libraryofbabel.info/bookmark.cgi?vfnkeaxl264 Volume 4 on Shelf 3 of Wall 3 of Hexagon [title too long to be inserted here] And this is only one location out of \(29^{2961}\) possible matches. It seems the monkey's quote is pretty well recited. Or maybe it is only because what he has written is not special enough? How about something with more structure? Something more unique? Like this poem by Shakespeare:

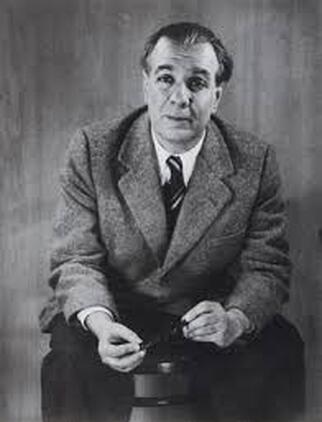

Title: urwoxny mae.fbcshvyxoqr Page: 143 Location: https://libraryofbabel.info/bookmark.cgi?l_usgwpzvthbvmrndxu..pw110 There are about \(80281895\) more unique matches of this poem in Babel. Shakespeare's poem is considerably harder to find compared to the monkey's text. It is no surprise though; It is a longer text with a more organized structure and an extremely rare wording configuration. So rare that so far in the written history only one man has managed to put them together this way. Yet, compared to all possible word configurations we can get, it is not that unique after all. The Lucky Pattern Most of the content of Library of Babel is seemingly garbage. But what is not garbage? What does separate a meaningful coherent sentence from a nonsensical one? Is it some sort of non-arbitrary order? Can that order be temporary, adaptive or even accidental? [the following needs reordering] To answer these questions we need to investigate the rules that define an order, and whether those rules are fundamental or just a set of constructs. But how those rules are set or discovered in the first place? One way to think about them is to consider them as a set of patterns persistent along the axis of observation: the pattern of changing seasons persisting along the time axis, the pattern of a falling object along the space-time axis, the pattern of words along the language axis, etc. The famous Infinite Monkey Theorem (monkeys accidentally producing Shakespearian masterpiece if randomly hitting the typewriter buttons for long enough time) was originally suggested to highlight the fact that any meaningful construct is a subset of a larger one. The one that is mostly meaningless. It is substantial to understand and accept the relationship between emerging patterns in subsets where the main set is mostly nonsensical. It is like trying to figure out how intelligence has emerged from chaos. Is it by design? Or is it a direct result of having an infinitely large space of arbitrary arrangements of atoms and just getting lucky? I am not suggesting an answer. But we should not easily discard the latter question because its answer is not as trivial as we tend to think it is.

Sean Carroll, a writer, speaker and physicist at Caltech says: Humans are not very good at generating random sequences; when asked to come up with a “random” sequence of coin flips from their heads, they inevitably include too few long strings of the same outcome. In other words, they think that randomness looks a lot more uniform and structureless than it really does. The flip side is that, when things really are random, they see patterns that aren’t really there. It might be in coin flips or distributions of points, or it might involve the Virgin Mary on a grilled cheese sandwich, or the insistence on assigning blame for random unfortunate events. So are we acting like Hot Hand gamblers when it comes down to our understanding of universe? The Stencil The thing is we seek and find and mistake a local repetition (as one of many ways of detecting structure and discovering laws of nature) with a global order. Our minds tend to extrapolate too often and too far. It is comforting to assume the laws of physics that seemingly hold true for the first 14 billion years, will continue to hold true for the next trillion trillion trillion trillion years. But as with any overly local model, there comes the risk of overfitting in the presence and overshooting in the future. If not 100% certain to happen, it is still a matter that needs serious precaution in constructing a model for making sense of things. We construct meaning. We choose to. We seek meaning to make sense of things, and the relation between things, because our survival depends on them, perhaps the same way that the gambler's life is desperately biased by taking luck for order. But those constructs are not more meaningful, nor meaningless for that matter, than any of other trillions of other ones that are not useful or compatible with our brain circuitry. It is like cutting out a stencil the only way we know how to cut, and filtering what we see through those patterns on the stencil. What we see makes sense to us because the patterns we cut out make sense to us. What we see makes sense not more than how the patterns we cut out make sense. There is no way to put down the stencil and survive the complexity of the world. We are addicted to it. We depend on it. But the constant struggle and the certitude of failure of not always being right can be frustrating. It can mislead us to superstition, impotent science or at the very least to a stressful state of mind... a constant fear of not understanding. That is why I particularly like what the the creator of Babel says: Those who tire of being constantly thwarted looking for meaning among the library’s babble can use reading its jumbled texts as a form of meditation. Eventually your mind learns no longer to search for or expect significance. P.S. Even in the short burst of mumbling on top of this page the monkey has spoken. Anglishize your eyes to see it.

0 Comments

|

Proudly powered by Weebly